A Legendary VC Has a Plan for Solving Climate Change

John Doerr’s new book, Speed and Scale: An Action Plan for Solving Our Climate Crisis Now, is a checklist for global action.

Every week, our lead climate reporter brings you the big ideas, expert analysis, and vital guidance that will help you flourish on a changing planet. Sign up to get The Weekly Planet, our guide to living through climate change, in your inbox.

It’s not perfect, but sometimes I think about the computer and internet revolution as an analogy for the energy transition. Each shift required electrifying huge parts of society. Each saw the need for crucial minerals increase and changed the geopolitical balance of power. And each sped up productivity while putting many people—secretaries, bank tellers, and human computers—out of work.

Even among the ranks of tech billionaires, John Doerr can claim to have had an unusually front-row view of that IT upheaval. Doerr began his career in 1975 selling semiconductors for a small and growing hardware start-up based in Santa Clara, California, called Intel. Five years later, he became a venture capitalist at the now-legendary firm Kleiner Perkins, where, over the next several decades, he provided early funding to Netscape, Amazon, and Google. He remains on Google’s board today, and he is a major Democratic donor.

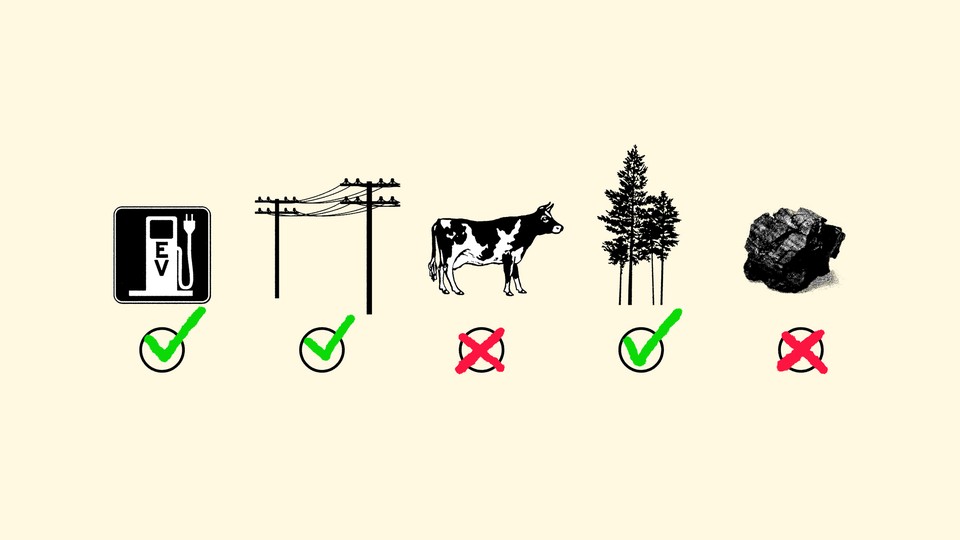

Like many others in Silicon Valley, he has recently refocused his attention on climate change. He has just published an interesting and unusual new book about it—Speed and Scale: An Action Plan for Solving Our Climate Crisis Now. (Much of the book is free to read on its website.) Where other climate books are exhortative or doom-laden, Doerr’s is straightforward. It is an airport business book about climate change in the form of a global checklist for climate action. It ticks through five top-line objectives that humanity must satisfy in order to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius. These objectives are clear and deceptively simple—they include "Decarbonize the power grid,” “Fix food,” and “Clean up industry.” Then the book lists four accelerants that will help humanity speed up its completion of those goals. These are deceptively simpler. They include “Win politics and policy,” “Turn movements into action,” and “Invest!”

That exclamation point appears in the book, too. It’s no surprise that Doerr, who has capitalist in his job title, sees a prominent role for capitalism in the transition. That can give him unusual perspective and a strange myopia: His decades at Kleiner Perkins have led him to see investment flows as part of a system of power to be manipulated and not, as many climate activists approach them, as an obstacle to be overcome.

“I don’t see how we solve this problem without harnessing the forces of capitalism,” he told me in an interview last month. “The best analogy I have in the book is what happened in World War II. The U.S. and Great Britain stopped manufacturing cars and appliances and for four years turned that capacity over to making, I think it was, 268,000 fighters and 20,000 battleships and a bazillion rounds of ammunition. We have to similarly make the right thing to do the profitable thing to do, so it becomes the probable outcome.”

This is the second time Doerr has sought to lead on climate change. In 2006, he held a private screening of An Inconvenient Truth for his family and friends. Afterward, at dinner, “we went round the table and some of my Republican friends said, ‘Looks like global warming is real, but I'm not sure it's man-made,’” he told me. “When it came to [my daughter] Mary, she looked straight at me and she said, ‘Dad, I’m scared and I’m angry. Your generation created this problem. You better fix it.’”

That call to action became Doerr’s calling card. He cited it in his 2007 TED Talk, in which he declared green technology to be “bigger than the internet … It could be the biggest economic opportunity of the 21st century.” He plowed $1 billion into the space, supporting more than 70 companies—many of which immediately proceeded to fail. Half a decade later, those clean-tech revolutionaries had been dwarfed by the very internet companies that Doerr had imagined they could overtake. Solar companies were hit particularly hard—Doerr supported eight of them, and seven went bankrupt—because China’s ability to manufacture low-quality solar panels at scale obviated demand for the more efficient but more expensive next-generation panels that the California start-ups had championed.

Today, his original climate-tech investments are worth $3 billion, a minor recoupment. (They would have been worth far more had he backed Tesla and not the now-defunct electric-vehicle start-up Fisker, which he called “probably the worst investment decision of my life.”) The recent surge in concern for the climate seems to have inspired him to return to the issue.

Although his top-line goals are extremely broad, if not simplistic—ah yes, all we have to do is fix food—that is by design: Doerr finds inspiration in Intel’s storied management culture, which set a broad objective for a business unit and then laid out the measurements-based key results needed to bring about that objective. And the book’s appeal lies in the directness of these goals—and in the research that Doerr and a small team led by his adviser, Ryan Panchadsaram, did in compiling them. (That team included the political strategist Alix Burns and the former New York Times reporter Justin Gillis. I should add that I know Panchadsaram; he was an adviser to the COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic, which I co-founded.)

So each of Doerr’s objectives is meant to eliminate a certain amount of emissions: The transportation sector is responsible for eight gigatons of climate pollution a year today, he says, but that number must shrink to two gigatons by 2050. This is essentially a more user-friendly version of the kind of economic-pathway modeling that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change runs in its reports. Each objective is then associated with several “key results”: To electrify transportation, EVs must achieve price parity with combustion-engine cars in the United States by 2024, and in China and India by 2030. (In Doerr’s parlance, that is Key Result 1.1.) Then half of new cars purchased worldwide must be EVs by 2030 (Key Result 1.2), and all new buses worldwide must be electric by 2025 (Key Result 1.3).

The regimented language of tech companies has suffused American workplaces, but now Doerr has applied it to a global political problem. And that is the book’s success and its mistake. Doerr and Panchadsaram have created a unified way of talking about solving climate change—for themselves, if no one else. Both will reference individual to-do items, such as “KR 4.2” or “KR 6.1,” in conversation. But the world is not a firm. Humanity cannot pursue initiatives single-mindedly like a company can, and Doerr’s “we”—the actor that is supposed to achieve EV price parity and ensure that all buses are electric by a certain year—does not actually exist.

It could exist, of course—that is an open political question. The book proposes several ways around this without describing the problem outright. One is the aforementioned “Invest!”: VC into private companies should swell from $13 billion a year to more than $50 billion a year, the book says. Its further idea to free up blocked policy routes is to elect more pro-climate officials (KR 8.2) and make the climate crisis a “top-two voting issue in the 20 top-emitting countries by 2025” (KR 8.1). And while the book cites encouraging case studies about how to achieve these political goals, the underlying issue—who is the political actor doing all this stuff?—isn’t a quibble; it is the central challenge of climate change. If we knew who the historical actor was, if we even had a “we” to solve the problem, then addressing climate change would be far more straightforward.

So Doerr and his colleagues support a carbon tax. “We have failed in our capitalistic system to put a price on externalities that are real and that are measurable,” he said. Their plan for fighting political opposition “is Key Result 7.2: End direct and indirect subsidy to fossil-fuel companies and for harmful agricultural practices,” he said. “The independent International Energy Agency said we’re going to have to end the use of fossil fuels. Period. Stop them—coal, natural gas, done.” What if fossil-fuel companies protest their own demise? Then “we defeat them in the marketplace; we defeat them in the legislature; we defeat them in the boardroom.” The successful campaign to install activist investors on the board of ExxonMobil, he added, shows that it can be done.

I mean, that is the plan: constant negotiation and political battle with opponents of decarbonization until the task is through. It’s not like I have a better idea how to do that—or who the “we” is either. And the book remains a useful guide: a systematic, holistic approach to thinking through the engineering problem of battling climate change, and a set of upgrades that should be achieved in order for us—whoever we are—to flourish.